The University of Massachusetts Cold Spring Orchard in Belchertown features more than 100 apple varieties, including many New England natives. (Russell Steven Powell photo)

IT SEEMS ONLY FITTING to celebrate native New England apples on New England Apple Day Wednesday, September 3. The New England state commissioners of agriculture will be visiting orchards today to mark the official launch of the 2014 fresh harvest. While some early season varieties are picked in August, most of the region’s apple crop ripens in September and October, with New England’s favorite apple, McIntosh, traditionally available soon after Labor Day.

Although less than 2 percent of the national apple crop is now grown here, New England continues to have a strong apple industry and an even richer apple-growing heritage. Dozens of apple varieties have been discovered or developed on New England soils, and many flourish today. A number of them have had illustrious histories and were once among the most widely planted in the Northeast.

Baldwin (Massachusetts, 1740), Northern Spy (Connecticut, 1800), and Rhode Island Greening (Rhode Island, 1600s) were the nation’s most popular and well-known apples a century ago. They eventually were surpassed by newer varieties that were more marketable and easier to grow, but they still can be found at many New England orchards.

In the 19th century, two varieties whose names combine superlatives with the Massachusetts towns in which they were discovered, Hubbardston Nonesuch (early 1800s) and Westfield Seek-No-Further (1700s), were popular well beyond the New England region.

Hubbardston Nonesuch apple (Bar Lois Weeks photo)

Hubbardston Nonesuch, also known as American Blush, is a large, late-season apple with heavy red streaking on yellow-green skin, with occasional russeting. Its dense, yellow flesh is juicy, and it has an exceptionally small core. Its complex flavor, more sweet than tart, is ideal for cider and fresh eating, although its flavor tends to fade in storage.

References to Hubbardston begin in the early 1830s, and it was popular throughout the Northeast for much of the 19th century. As late as 1905, S. A. Beach in the classic work, Apples of New York, recommended Hubbardston for commercial orchards. But it is a difficult apple to grow, and only survives as a rare heirloom despite its rich flavor.

Porter apple (Bar Lois Weeks photo)

Porter is another Massachusetts native that once enjoyed widespread popularity. A medium, round, early season apple, apple, it has a yellow-green skin with a peach-colored blush. Its cream-colored flesh is tender, aromatic, and juicy. Its flavor is sweeter than tart, and it retains its shape and flavor when cooked.

It was discovered by the Rev. Samuel Porter in Sherburne around 1800, and was grown locally until about 1850, when its popularity spread to Boston and it began to be cultivated in other parts of the country. Despite its virtues as an eating and cooking apple, though, it, too, proved too difficult to grow for sustained success.

In his 1922 book Cyclopedia of Hardy Fruits, Ulysses P. Hedrick wrote, “A generation ago Porter took rank as one of the best of all yellow fall apples. If the fruits be judged by quality, the variety would still rank as one of the best of its season, but the apples are too tender in flesh to ship, the season of ripening is long and variable, and the crop drops badly.

“Porter must remain, then, an apple for the connoisseur, who will delight in its crisp, tender, juicy, perfumed flesh, richly flavored and sufficiently acidulous to make it one of the most refreshing of all apples.” It is also known as Summer Pearmain and Yellow Summer Pearmain.

Tolman Sweet apple (Bar Lois Weeks photo)

Tolman Sweet is a late-season apple, medium-sized, pale-yellow in color with a red or green blush. It sometimes has patches of russet, or a line running from top to bottom. Its white flesh is crisp and moderately juicy, and its unusual flavor is sweet and pear-like, but with some tartness. It is considered especially good in cooking and in cider.

Tolman Sweet may be a cross of Sweet Greening and Old Russet discovered in Dorchester, Massachusetts, but its origin is unclear. It was first cited in 1822, and it remained popular well into the 20th century. Its trees are exceptionally hardy, making it a good choice in Northern climes, but Tolman Sweet bruise easily, limiting its commercial appeal.

Sheep’s Nose apple (Bar Lois Weeks photo)

Another old New England favorite is Sheep’s Nose, from Connecticut. Also known as Black Gilliflower or Red Gilliflower, its names refer to its pronounced conical shape and deep ruby color, respectively. Often a striking solid red in color, it can have patches of green. Opinions about its mild, sweet-tart flavor are mixed. While aromatic, its dense flesh lacks much juice, and it becomes dryer in storage. It is good in cooking, though, especially in applesauce.

Whatever its flaws, Sheep’s Nose has had a small but steady following for more than two centuries, having been cited in New England as early as the Revolutionary War.

Granite Beauty apple (Bar Lois Weeks photo)

Granite Beauty is a large, late-season apple, round, ribbed, with red patches and stripes over a yellow skin. Its cream-colored flesh is crisp and juicy, and it has a rich flavor, more tart than sweet, with hints of coriander or cardamom.

Zephaniah Breed, who named Granite Beauty, wrote in the late 1850s, “no orchard is considered complete here unless it contains a good share of these trees. A good fruit grower here says he would sooner do without the Baldwin than the Granite Beauty.”

Breed published this account of the apple in the New Hampshire Journal of Agriculture:

“Years ago, soon after the first settlers located upon the farm we now occupy, they paid a visit to their friends in Kittery (now Elliott), Maine, on horseback, that being the only means of conveyance then in vogue.”

When ready to return home, Dorcas Dow “needing a riding whip, she was supplied by pulling from the earth, by the side of the road, a little apple tree. With this she hurried her patient and sure-footed horse toward her wild-woods home” in Weare, New Hampshire, then known as Halestown.

“An orchard being in ‘order’ about that time, the little tree was carefully set and tended, and when it produced its first fruit it was found to be excellent, and Dorcas claimed it as her tree. When nephews and nieces grew up around her, the apple was called the Aunt Dorcas apple.”

As Dorcas grew older, her grandchildren gave the apple the name of Grandmother. In another part of the town it was called the Clothesyard apple.

Maine’s contribution to the apple world includes the heirloom Black Oxford and a newer discovery, Brock.

Black Oxford apple (Bar Lois Weeks photo)

Black Oxford is Maine’s most famous apple, but like Brock it is little known or grown outside the state. Black Oxford is named for its distinctive dark, purple-red skin, with occasional green highlights and prominent white lenticels.

It is medium-sized and round, and its dense, white flesh has a tinge of green, and is moderately juicy. An all-purpose, late-season apple, its flavor is balanced between sweet and tart, and it is considered especially good in pies and cider. Its keeps exceptionally well, and its flavor becomes sweeter and more complex in storage.

According to George Stilphen, author of The Apples of Maine (1993), Black Oxford “was found as a seedling by Nathaniel Haskell on the farm of one Valentine, a nail maker and farmer of Paris in Oxford County, about 1790 and the original tree was still standing in 1907, the farm being then owned by John Swett.”

Brock apple (Bar Lois Weeks photo)

Brock, like Black Oxford, is a late-season apple. It is large, round or with a boxy shape, mostly red in color with a green or yellow blush. Its crisp, juicy, cream-colored flesh is mostly sweet, with a little tartness.

Brock is a cross between Golden Delicious and McIntosh, developed in 1934 by Russell Bailey, a longtime plant breeder at the University of Maine, and introduced commercially in 1966. It was named for grower Henry Brock of Alfred, Maine, one of the apple’s trial growers. The only variety developed at the University of Maine Cooperative Extension at Highmoor Farm in Monmouth, Brock has the same parentage as the Canadian apple Spencer, with distinctly different results.

Two recent New England apples that have enjoyed greater commercial success are Hampshire and Marshall McIntosh.

Hampshire apple (Bar Lois Weeks photo)

Hampshire is a large, late-season apple, nearly solid red in color, with crisp, juicy, cream-colored flesh. Although its flavor is less intense, Hampshire resembles McIntosh: more tart than sweet, tender flesh and a thin skin, and a rich aroma. It is a good all-purpose apple, and it stores well.

Hampshire is a chance seedling discovered in 1978 by Erick Leadbeater, then owner of Gould Hill Farm in Contoocook, New Hampshire. Its parentage is unknown, but it was found in a block of trees containing several varieties, including Cortland, McIntosh, and Red Delicious. It was released commercially in 1990.

Marshall McIntosh apple (Bar Lois Weeks photo)

Marshall McIntosh is a medium, round, early season apple with red skin and green highlights. It, too, resembles its McIntosh parent (its other parent is unknown) for its tender flesh, juiciness, aroma, and sweet-tart flavor. It ripens before McIntosh, though, and it has more red color

Marshall McIntosh was discovered in 1967 at Marshall Farms in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, and originally propagated by Roaring Brook Nurseries of Wales, Maine.

Find orchards that grow these native apples – visit New England Apples and follow the link “Find an Apple Orchard” to search by state or variety.

* * *

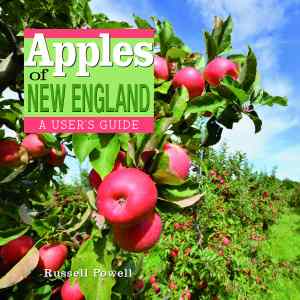

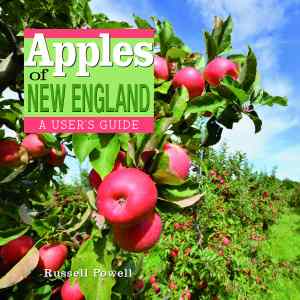

MORE INFORMATION about these and other apple varieties discovered in New England — such as America’s oldest named variety, Roxbury Russet (1635), and Davey (1928) from Massachusetts, and Vermont Gold (1980s) from Vermont — can be found in Apples of New England: A User’s Guide (The Countryman Press).

MORE INFORMATION about these and other apple varieties discovered in New England — such as America’s oldest named variety, Roxbury Russet (1635), and Davey (1928) from Massachusetts, and Vermont Gold (1980s) from Vermont — can be found in Apples of New England: A User’s Guide (The Countryman Press).

A new book by Russell Steven Powell, Apples of New England, includes photographs and descriptions of more than 200 apple varieties grown, sold, or discovered here, plus a history of apple growing in the region spanning nearly four centuries. Photographs are by Bar Lois Weeks, executive director of the New England Apple Association.

In addition to extensive research, Powell interviewed senior and retired growers and leading industry figures from all six New England states, and obtained samples of many rare varieties at the preservation orchard maintained by the Tower Hill Botanic Garden in Boylston, Massachusetts.

A chapter on John Chapman (“Johnny Appleseed”), for the first time links him with another Massachusetts native, Henry David Thoreau, as the fathers of American wild apples, Chapman for planting them, Thoreau with his pen.

Apples of New England is intended for use by all apple lovers, whether they are visiting the orchard, farm stand, grocery store, an abandoned field or a back yard — or in the kitchen. The descriptions include detailed information on each apple’s flavor and texture, ripening season, and best uses, as well as age, parentage, place of origin, and unusual histories.

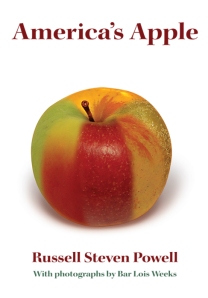

Powell has worked for the nonprofit New England Apple Association since 1996, and served 13 years as executive director from 1998 to 2011. He is now its senior writer. He is the author of America’s Apple (Brook Hollow Press, 2012), a book about apple growing in the United States.

Powell has worked for the nonprofit New England Apple Association since 1996, and served 13 years as executive director from 1998 to 2011. He is now its senior writer. He is the author of America’s Apple (Brook Hollow Press, 2012), a book about apple growing in the United States.

America’s Apple is now available in paperback for $19.95 as well as hard cover ($45.95). Visit Silver Street Media or Amazon.com to order online, or look for it at your favorite orchard or bookstore.

* * *

Powell will read from and sign copies of Apples of New England in a presentation at the Keep Homestead Museum, 110 Main St., Monson, Massachusetts, this Sunday, September 7, at 1:30 p.m. The event is free and open to the public.

Read Full Post »

Apples of New England (Countryman Press) is an indispensable resource for anyone searching for apples in New England orchards, farm stands, or grocery stores — or trying to identify an apple tree in their own backyard.

Apples of New England (Countryman Press) is an indispensable resource for anyone searching for apples in New England orchards, farm stands, or grocery stores — or trying to identify an apple tree in their own backyard. America’s Apple (Brook Hollow Press) tells a rich and detailed story about apple growing in America, from horticulture to history to culinary uses. Powell writes about the best ways to eat, drink, and cook with apples. He describes the orchard’s beauty and introduces readers to some of the family farms where apples are grown today, many of them spanning generations.

America’s Apple (Brook Hollow Press) tells a rich and detailed story about apple growing in America, from horticulture to history to culinary uses. Powell writes about the best ways to eat, drink, and cook with apples. He describes the orchard’s beauty and introduces readers to some of the family farms where apples are grown today, many of them spanning generations.