Fresh apples for sampling at Clarkdale Fruit Farms, Deerfield, Massachusetts, during Franklin County CiderDays (Bar Lois Weeks photo)

TWICE A DAY at least I reach into a paper bag in my refrigerator and pull out an apple. It could be any color, size, or shape — I like to be surprised. I take an apple on my morning and afternoon walks, where it can be savored in its natural environment, without distraction.

An apple is perfect for walking, clean and compact, fitting neatly in my pocket, giving me a sweet energy boost and fresh juice along the way. Apples work on all the senses, beautiful to behold (especially in contrast with November’s muted landscape) and lightly perfuming the air, their smooth, round or conical shape weighing comfortably in my hand.

While the last New England apples have been picked, the bounty of the harvest will last until late spring, at least. During the fresh harvest I was able to amass a wide variety of my favorite apples from around New England, which will supply my walks at least through Thanksgiving.

From my orchard visits in October I picked up small bags of Baldwin, Northern Spy, Rhode Island Greening, plus Honeycrisp, Jonagold, and McIntosh. I had some Gala, Empire, Macoun, and a few Silken left over from our booth at the Eastern States Exposition (“The Big E”) in September.

One bag is filled with heirloom varieties like Esopus Spitzenburg, Ribston Pippin, and Roxbury Russet. There are a few loose stragglers on the refrigerator’s shelves, a Golden Delicious one day, Suncrisp the next. I never know what I will retrieve when I reach in.

Monday I ate a Jonagold in the morning, and a Macoun in the afternoon — two of my favorite fresh eating apples. There are mixed reports about the storage qualities of Jonagold, a 1968 cross of Golden Delicious and Jonathan, but this one, purchased a month ago, held up beautifully, crisp and loaded with juice, with its characteristic flavor, sweet with a little tartness.

After a similar time in storage, the Macoun, the offspring of McIntosh and Jersey Black parents introduced in 1923, remained crisp, and its flavor was rich and complex, with its spicy, strawberry notes more pronounced than ever.

Tuesday I ate two heirlooms, McIntosh from Canada (1801), and Northern Spy (1840 New York, from seeds from Connecticut).

The Mac was outstanding, early in its flavor “arc” that sees the apple gradually sweeten and soften over several months. It had been two months since this McIntosh was harvested, and much of the apple’s tartness remained intact, giving it a rich flavor as beguiling as fresh-picked and spicier, more complex.

The pink Northern Spy was huge, firm, and juicy, its initial tartness gradually transforming into something broader and deeper. It is easy to see why this apple was a favorite for nearly a century despite being somewhat unreliable and difficult to grow, as it stores well, and is equally good for fresh eating and baking.

I began Wednesday with a giant Honeycrisp that had been sitting in the crisper drawer for about two months.

While still juicy, its flavor was unexceptional, certainly nothing like what the apple has become famous for since it hit the marketplace in 1991, from a 1961 cross of Keepsake and an unnamed seedling at the University of Minnesota.

Some Honeycrisp store better than others, depending on where they were grown and when they were picked, but it is an apple that is appreciably better eaten fresh. A good Honeycrisp can also be almost solid pink-red in color, much like Northern Spy.

I ended the day with a Baldwin, one of New England’s oldest varieties, dating back to 1740 in Wilmington, Massachusetts. Baldwin was the region’s most popular apple for nearly a century before McIntosh’s ascendancy in the early 1900s.

The Baldwin I ate was the crispest and tartest of the six apples I tasted during the three days (it may have been the last of these varieties to be picked). Beneath its round, nearly solid vermillion skin, freckled with cream-colored pores, or lenticels, the Baldwin’s crisp, juicy flesh was pleasingly tart at first but finished sweeter, ending in sublime flavors of pineapple and melon.

* * *

The view from Clarkdale Fruit Farms, Deerfield, Massachusetts, early November (Bar Lois Weeks photo)

HERE ARE A FEW ways to get the most from your fresh apples:

When trying a new variety, always purchase at least four apples. Eat two of the apples a few days apart, within a week of purchase. No two apples are exactly alike. Subtle flavors like vanilla, nuts, or mango can vary in intensity from apple to apple, and sometimes can be hard to detect. By trying two fresh apples, you are more likely to experience the variety’s full range of flavors.

Place the other two apples in your refrigerator, and mark the date they were purchased or picked. Ideally, seal the apples in plastic bags and store them in your crisper drawer. As long as they are kept cold, though, most apples keep pretty well in a paper bag. Either bag helps them retain moisture, and keeps them from absorbing odors from foods around them.

Wait a month before tasting the first of these stored apples. Note if there is an appreciable difference in flavor and texture, good or bad. Some apples peak in flavor around this time.

Many varieties follow a similar ripening arc, albeit it at different rates, gradually losing some of their initial tartness and becoming sweeter, more complex, and juicier over time. The same variety can be appreciated in different seasons for different reasons.

From a crisp, tart green apple in late September, Shamrock gets progressively spicier and juicier for about a month before it begins to break down. The flesh of the Connecticut heirloom Sheep’s Nose is dry at harvest, but becomes mellower and juicier after a month or more in storage.

Idared’s best flavor will not emerge until the new year, when it excels in pies and in cider. The flavor of Suncrisp is said to improve in storage, but I wouldn’t know — I enjoy their sweet-tart, citrusy taste so much eaten fresh that I cannot seem to make one last long enough to find out. I have one left in my refrigerator this year, and I am determined to make it last to December, at least.

If your apple has held up well for 30 days, leave the remaining one in the refrigerator for another month (or more) before tasting it. Fuji is famous for its storage qualities. Russeted-covered apples like Ashmead’s Kernel and Roxbury Russet are well known for developing richer, more complex flavors in storage, sometimes months after they have been harvested.

Obviously, the apples available now in grocery stores, farmers markets, orchards, and farm stands, were picked weeks ago. But they have been maintained in either regular, or controlled atmosphere (CA) storage, retarding their ripening process.

Stored properly — meaning kept cold — the apples may be slightly less crisp than the day they were picked, but not much. You can test an apple’s ripening qualities any time you make your purchase.

Don’t reject perfectly good fruit. You can’t always judge an apple by its skin. Most surface blemishes on an apple are harmless and easily removed, such as a patch of apple scab, a dent from hail, or spot russeting. An otherwise fine apple can be misshapen because it rested on a branch as it grew. The apple’s flavor is in no way impaired.

All apples bruise if treated roughly, and some varieties are more susceptible than others. A thin-skinned apple like Silken or a tender-fleshed one like McIntosh require special care in handling. But a bruise here and there on an apple’s surface can easily be ignored, avoided, or removed.

A perfectly good apple often awaits beneath that less-than-perfect exterior. The Galas from The Big E are looking a little wrinkly on the outside, but their flesh remains firm and their flavor is as good as ever. The color of Galas changes in storage, too. It typically has patches of yellow at harvest, and gradually deepens to a rich red-orange.

Rub the apple, eat the skin. While apples leave the orchard and packinghouse clean, like all produce it is best to wash them off before eating, mostly because of the possibility of contamination by human handlers. You never know who may have previously picked up that apple in the bin.

The natural film or “bloom” on an apple, sometimes mistaken for pesticide residue, helps the apple retain moisture. Some of the bloom gets washed off in the packinghouse, and in some cases a drop of wax is applied to replenish it and give the apples a shine. Both the natural bloom and the cosmetic wax are harmless.

The majority of the chemicals used to treat apple pests and disease are applied in the spring and early summer, some before the fruit is even formed. Most residual traces of chemicals are washed off by rain over the summer, and apples entering the packinghouse are first dunked in a tank of water where they float for ten feet or more before entering the packing line, where they will be further buffed and brushed along the way.

But it’s always a good idea to clean your fruit before you eat it. The beauty of the apple is that you don’t need water to wash it— just rub it on your shirt, especially convenient when outdoors.

The peel and the flesh just beneath it contain much of the apple’s nutrients, so there are compelling reasons to eat it. That’s automatic for most people eating a fresh apple, but requires some rethinking on the part of many bakers and cooks. Prepared properly, though, apple skins can add color as well as nutrients to any dish.

Make sure your apples are ripe. It’s good to know what you are getting. The best way to tell if an apple is ripe is by examining its seeds. The apple should not be picked until the seeds are dark brown, almost black, in color.

If you find that some of your apples were not fully ripe when picked, you can eat them without harm. They are likely to be more tart than usual, though, may not store as well, and may have inferior flavor.

I purchased some Ginger Golds in August, and when I cut several of them open, their seeds were white, not brown. The apples tasted alright, but nowhere near as good as Ginger Golds I have had in the past.

Today, two-and-a-half months later, the apples have slowly ripened in my refrigerator, and the seeds are now medium brown. But the ripening has been uneven; the flavor is not much improved, the flesh is beginning to go soft, and they are not very juicy. Reluctantly, I’ll have to throw them out.

* * *

For more information about New England apples, including where to find them, visit New England Apples.

* * *

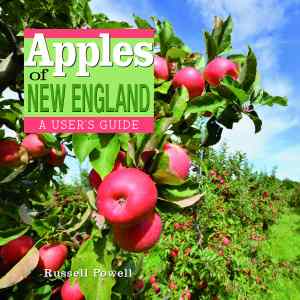

APPLES OF NEW ENGLAND (Countryman Press, 2014), a history of apple growing in New England, includes photographs and descriptions of more than 200 apple varieties discovered, grown, or sold in the region. Separate chapters feature the “fathers” of American wild apple, Massachusetts natives John Chapman (“Johnny Appleseed”) and Henry David Thorea; the contemporary orchard of the early 21st century; and rare apples, many of them photographed from the preservation orchard at Tower Hill Botanic Garden in Boylston, Massachusetts.

APPLES OF NEW ENGLAND (Countryman Press, 2014), a history of apple growing in New England, includes photographs and descriptions of more than 200 apple varieties discovered, grown, or sold in the region. Separate chapters feature the “fathers” of American wild apple, Massachusetts natives John Chapman (“Johnny Appleseed”) and Henry David Thorea; the contemporary orchard of the early 21st century; and rare apples, many of them photographed from the preservation orchard at Tower Hill Botanic Garden in Boylston, Massachusetts.

Author Russell Steven Powell is senior writer for the nonprofit New England Apple Association after serving as its executive director from 1998 to 2011. Photographer Bar Lois Weeks is the Association’s current executive director.

Available in bookstores everywhere.

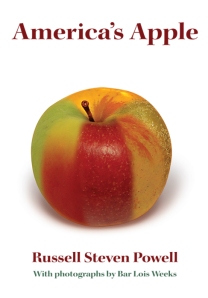

AMERICA’S APPLE, (Brook Hollow Press, 2012) Powell’s and Weeks’s first book, provides an in-depth look at how apples are grown, eaten, and marketed in America, with chapter on horticulture, John Chapman (aka Johnny Appleseed), heirloom apples, apples as food, apple drinks, food safety insects and disease, labor, current trends, and apple futures, with nearly 50 photographs from orchards around the country.

AMERICA’S APPLE, (Brook Hollow Press, 2012) Powell’s and Weeks’s first book, provides an in-depth look at how apples are grown, eaten, and marketed in America, with chapter on horticulture, John Chapman (aka Johnny Appleseed), heirloom apples, apples as food, apple drinks, food safety insects and disease, labor, current trends, and apple futures, with nearly 50 photographs from orchards around the country.

The hardcover version lists for $45.95 and includes a photographic index of 120 apple varieties cultivated in the United States. America’s Apple is also available in paperback, minus the photograph index, for $19.95, and as an ebook.

Available at numerous bookstores and orchards, and Silver Street Media, Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, and other online sources. For quantity discounts, email newenglandapples@verizon.net.